A defining characteristic of the Nordic countries is their ability to combine strong economic performance with relatively low levels of inequality. The Nordics appear to have developed a social and economic model that successfully merges prosperity with equality. A feature in The Economist even described the Nordic approach to economic organisation as “the next supermodel” (The Economist 2013). In a recent paper (Mogstad et al. 2025), we critically examine this claim. Using both theory and empirical evidence, we explore how the Nordic model functions, investigate why these countries maintain low inequality, and consider what lessons – if any – can be drawn for other economies.

While several macroeconomic surveys of the Nordic model exist (Lundberg 1985, Lindbeck 1997, Andersen et al. 2007), our study takes a different approach. Rather than focusing on macroeconomic performance, labour market dynamics, or political economy, we emphasise economic equality. Adopting a more eclectic and data-driven perspective, we assess multiple competing explanations for the Nordic model’s apparent success in balancing prosperity and equality.

The pillars of the Nordic model

We identify four key pillars of the Nordic model of economic organisation:

- Substantial public investment in family policies, education, and health services, ensuring broad access to essential services.

- Influential labour unions with coordinated wage-setting across and within industries.

- High public expenditure on social insurance systems that protect individuals against income losses due to unemployment, disability, and illness.

- High and progressive taxation of labour income, complemented by subsidies for services that support employment.

A central question in our analysis is the extent to which each of these pillars contributes to Nordic equality.

Income equality in the Nordic countries

A key observation is that a more equal pre-distribution of earnings – rather than income redistribution – is the primary reason for lower income inequality in the Nordic countries compared to the US and the UK. While taxes and transfers contribute to income equality, the most significant factor is the relatively equal distribution of pre-tax market income, particularly labour earnings, in the Nordic countries.

Equality in labour earnings can result from three sources: a more equal distribution of hours worked, less variation in hourly wages, or lower covariance between hours and wages. The main reason for lower earnings inequality in the Nordic countries compared to the US and the UK is equality in hourly pay. While lower variance in hours worked and covariance between wages and hours contribute, the compression of hourly wages explains most of the difference in earnings inequality.

It is wage compression within gender, rather than between men and women, that explains why the Nordic countries have a more equal hourly wage distribution than the US and the UK. Although discussions on income inequality in the Nordics often focus on gender equality, the within-gender component is far more significant. The gender wage gap is about 30% lower in the Nordics than in the US, but accounts for less than 2% of the difference in hourly wage dispersion between the two regions.

Compressed wages

We examine several possible explanations for the low dispersion in hourly wages in the Nordic countries. One possibility is that universal access to essential services – such as family and health services and education, including university – reduces variation in labour market skills. In this case, wage equality arises because Nordic workers enter the labour market with less variation in productive skills. An alternative explanation we consider is that influential unions and centralised and coordinated wage-setting may lead to lower returns to skills, resulting in a compressed wage distribution.

To distinguish between these explanations, we review the extensive literature on the effects of welfare policy extensions in the Nordic countries. While some studies find that universal welfare programmes have positive impacts on families at the lower end of the socioeconomic scale, these effects are modest and cannot account for the large differences in hourly wage dispersion between the Nordics and the US.

A more direct test of these explanations uses the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) data, which include information on both work-related skills and hourly wages. While the skills distribution is slightly more compressed in the Nordic countries, the difference in hourly wage dispersion is much larger, suggesting that low returns to skills are the main driver of wage equality in the Nordics.

This is confirmed by a formal decomposition analysis, showing that nearly all the differences in hourly wage inequality between the Nordic countries and the US can be explained by differences in the skill premium and other characteristics. In contrast, differences in workforce composition by skills and other characteristics explain little, if anything, in this regard.

Wage setting in the Nordics

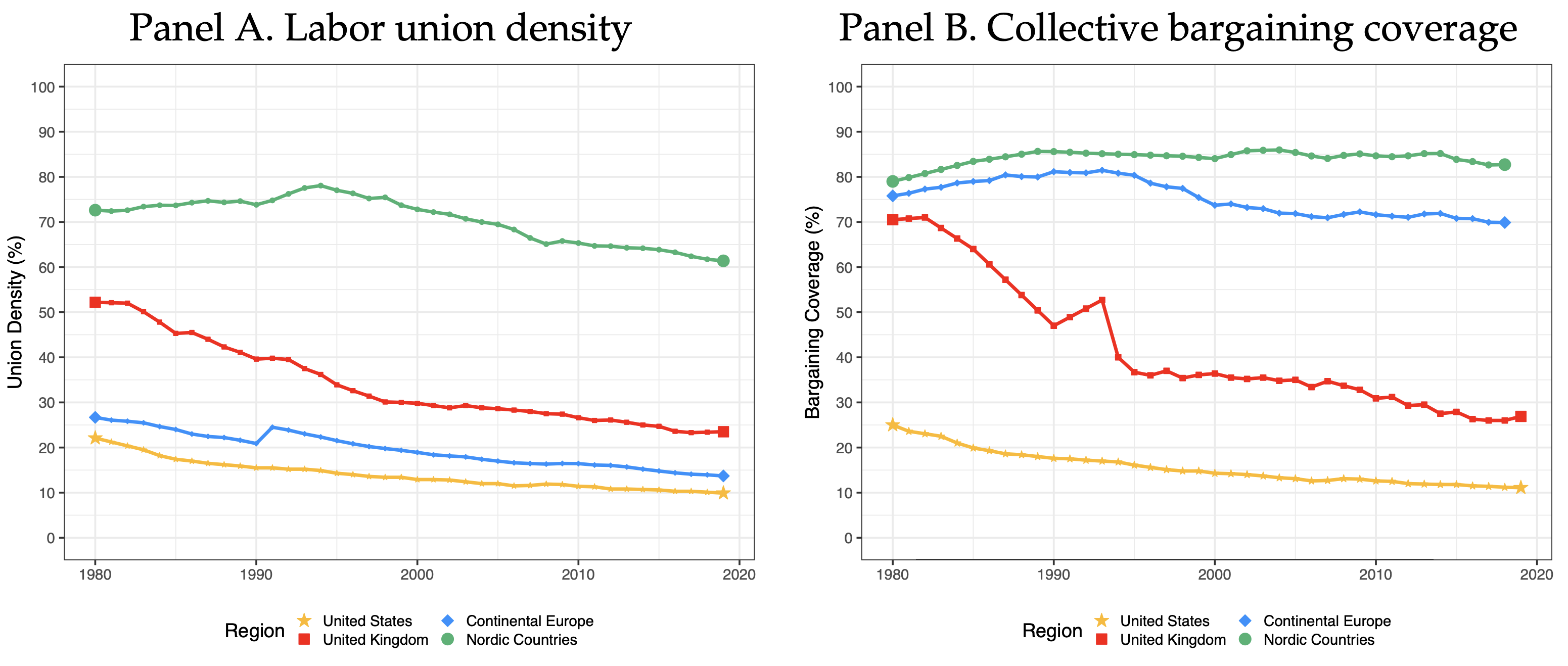

The compression of wages in Nordic countries stems from their distinctive wage-setting models. While the specific practices vary across these nations, they all have high union density and strong coordination in wage bargaining. Figure 1 illustrates that there has been a general decline in the degree of unionisation and in the fraction of workers who are covered by collective bargaining agreements in the western world over the last 40 years. The Nordic countries stand out with a high initial level of unionisation and coverage and a relatively modest decline over time.

Figure 1 Trends in union density and bargaining coverage

Notes: Panel A shows the fraction of union members and panel B the fraction of workers covered by collective bargaining agreements. ‘Continental Europe’ includes France, Germany, Spain, and Portugal, and ‘Nordic Countries’ includes Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland.

Source: Bhuller et al. (2022).

Wage setting in the Nordic countries follows a two-tier system: sectoral negotiations establish wage floors, followed by local bargaining at the firm level. This system fosters wage coordination, leading to wage compression within and across industries. Using Norwegian data, we explore the relationship between wages and labour productivity. Firm productivity is measured as revenues minus input costs and inventory changes, while wage floors and drifts are adjusted for worker characteristics (e.g. age, education).

In Figure 2, Panel A highlights intra-industry differences in productivity, wage floors, and wage drift. Workers are sorted by productivity, from the most to least productive firms. Labour productivity and wage floors are indexed in Norwegian krone (NOK) along the left vertical axis, with wage drift shown on the right. Two key insights emerge: first, sectoral bargaining sets a common wage floor; second, local bargaining introduces wage variation, as more productive firms can offer higher wage drifts. Less productive firms pay wages near their productivity level, while highly productive firms pay relatively lower wages, generating quasi-rents.

Figure 2 Labour productivity, wage floors, and wage drift

Notes: Panel A shows firm/worker-level measures, adjusted for differences across collective bargaining agreements. Panel B displays agreement-level averages. Labour productivity, wage floors, and wage drift are measured biennially from 2010 to 2018, using firms with at least five workers and positive value added over a five-year period. The sample is truncated at the 5th and 95th percentiles of labour productivity. Wage floors and drifts are measured for full-time workers aged 25–60 who remained in the same job, with wages winsorised at the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles.

Source: Bhuller et al. (2022).

Nordic exceptionalism?

We have argued that income equality in Scandinavia largely stems from wage compression achieved through highly coordinated wage-setting. This raises important questions: What are the implications for productivity and growth? Can this model be successfully emulated by other countries?

The answer is contested. One perspective suggests that the Nordics benefit from innovation and risk-taking driven by less-equal countries. If all nations adopted the Nordic model, global innovation and growth might decline (Acemoglu et al. 2017).

Another view argues that wage compression and social insurance can stimulate innovation, productivity, and growth. By raising the cost of low-skilled labour and lowering costs for high-skilled workers, these policies may encourage technological adoption and phase out inefficient firms.

Additionally, they help share risks and compensate workers affected by structural changes, reducing resistance to new technologies, global trade, and competition.

Research on this topic remains inconclusive, with most evidence being correlational or circumstantial. Advancing this discussion requires stronger integration between data and theoretical frameworks than is currently seen in labour economics. To make real progress, it is essential to identify and estimate models where skills, labour supply, capital investment, wages, and profits are determined simultaneously. Without such models, understanding whether the Nordic model is replicable – or even desirable – remains elusive.

References

Acemoglu, D, J A Robinson and T Verdier (2017), “Asymmetric growth and institutions in an interdependent world”, Journal of Political Economy 125(5): 1245-1305.

Agell, J and K E Lommerud (1993), “Egalitarianism and growth”, The Scandinavian Journal of Economics: 559-579.

Andersen, T M, B Holmström, S Honkapohja, S Korkman, S H Tson and J Vartiainen (2007), “The Nordic Model. Embracing globalization and sharing risks”, ETLA B.

Bhuller, M, K O Moene, M Mogstad and O L Vestad (2022), “Facts and fantasies about wage setting and collective bargaining”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 36(4): 29-52.

Lindbeck, A (1997), “The swedish experiment”, Journal of Economic Literature 35(3): 1273-1319.

Lundberg, E (1985), “The rise and fall of the Swedish model”, Journal of Economic Literature 23(1): 1-36.

Moene, K O and M Wallerstein (1997), “Pay inequality”, Journal of Labor Economics 15(3): 403-430.

Mogstad, M, K G Salvanes and G Torsvik (2025), “Income Equality in The Nordic Countries: Myths, Facts, and Lessons”, NBER Working Paper 33444.

The Economist (2013), “The next supermodel”, 2 February.